/ posts / By Artem Zaporozhets

Introduction: The Anatomy of a “Successful Failure”

In the world of game development, we often celebrate clear-cut victories: the chart-topping launch, the record-breaking revenue, the soaring retention curves. But some of the most profound lessons don’t come from unmitigated success. They come from the projects that haunt you—the ones where your systems were flawless, your math was perfect, your team was brilliant, but the game still fell short.

This is one of those stories.

My name is Artem Zaporozhets, and I’m a Lead Game Designer with over a decade of experience in building F2P economies. This is the case study of Playtagon, a 3v3 third-person MOBA project that taught me more about the harsh realities of game development than any straightforward success ever could. It’s a story about the intricate dance between game balance and soft monetization, the critical, often underestimated, power of the First-Time User Experience (FTUE), and how a project’s unexpected outcome can become a powerful catalyst for professional growth.

We designed a sophisticated, player-friendly economy inspired by giants like Clash Royale. Our mathematical models were so accurate that during playtests, players behaved and monetized exactly as we predicted. Yet, the project was shelved.

Why? Because a single, devastating variable—a premature playtest—collided with our development plan, revealing a truth every developer must face: a perfect system inside a broken wrapper is still a broken product. This is a deep dive into how we built that system, why it technically succeeded, and why the game ultimately failed.

The Challenge: Inheriting a Broken Kingdom

I joined the Playtagon project at its third iteration. To say it was in a state of disarray would be an understatement. The previous team had failed to deliver, and initial playtests had yielded abysmal results. A new team was being assembled from scratch, and I was brought on as the Lead System Designer to make sense of the chaos.

The initial state of the game was a textbook example of a system crash:

- A Disconnected Experience: The meta-gameplay (progression, collection) and the core-gameplay (the 3v3 MOBA combat) were completely unrelated. There was no meaningful loop connecting what you did outside of a match to what you did inside one.

- A Solved, Unbalanced Core: The MOBA design was so imbalanced that players could identify the single most effective hero almost immediately, destroying any strategic depth.

- A Theoretically Unprofitable Economy: The game monetization model was, paradoxically, designed in a way that gave players everything they needed, creating zero motivation to ever spend money. The internal economy was fundamentally broken.

- A Rigid, Unfixable Backend: We couldn’t simply tweak the numbers; we had no tools to rebalance the economy or adjust the gameplay loops.

The project looked like a game, but it wasn’t one. It failed to create desire, motivation, or any long-term goals. We stood before a monumental task: not just to adjust a game, but to perform a full system transplant and build a new soul for it. The publisher’s business goal was simple: make it work. Make it a real game with the potential for longevity and profitability.

The Philosophy: “Befriending the Player” with Clash Royale-Inspired Soft Monetization

Faced with a blank slate, we had to define a new philosophy. Our team was composed of people who deeply loved games, and the idea of creating a frustrating, coercive pay-to-win experience was antithetical to our values. We decided to embrace one of the most challenging but rewarding models: soft monetization.

Our philosophy was simple: we wanted to befriend our players for years.

This meant no hard paywalls. No content would ever be locked exclusively behind a purchase. A player could, in theory, unlock everything in the game for free. Our game monetization strategy would be built on desire, not coercion. We would create a system so engaging that players would want to spend money to get more of something, or get it faster, because it was a satisfying choice, not a mandatory toll.

My primary inspiration for this was Clash Royale, a masterclass in soft monetization. The core principle I adapted was the careful management of surplus and deficit.

Our core hypothesis was this:

- Early Game (Surplus): At the beginning of their journey, players should be showered with rewards. We needed to provide a surplus of content and resources to facilitate discovery, experimentation, and a strong sense of progress.

- Mid-Game (Skill Building): As players become more competent, the firehose of rewards should slow. This controlled scarcity encourages them to focus, develop their skills with a few favorite heroes, and make strategic choices.

- Late Game (Aspirational Deficit): In the long term, we would create a clear and desirable “target state” of progression that players would aspire to. The free-to-play path would get them there, but slowly. The “deficit” between their current state and their desired state would be the primary driver for our soft monetization.

This philosophy would dictate every aspect of our new system, from reward distribution to the design of the core progression entities.

The Architecture of Desire: Building the System

Translating this philosophy into a concrete system design case study requires looking at the architecture we built.

1. The Key Entities:

- Heroes: The collectible characters at the heart of the MOBA.

- Talents: Our core progression vector. Instead of just leveling up a hero, players collected and upgraded specific Talents that could be equipped to them. This created a deeper, more customizable progression.

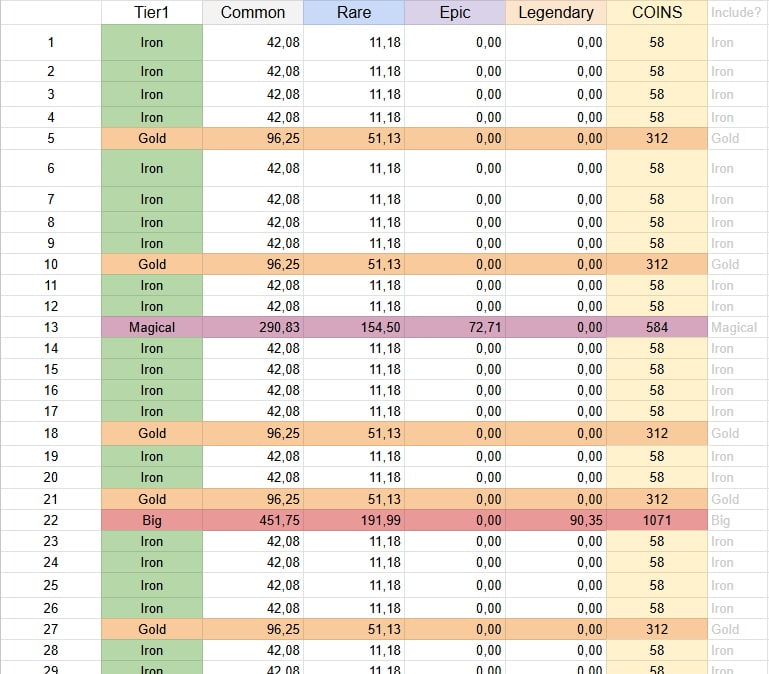

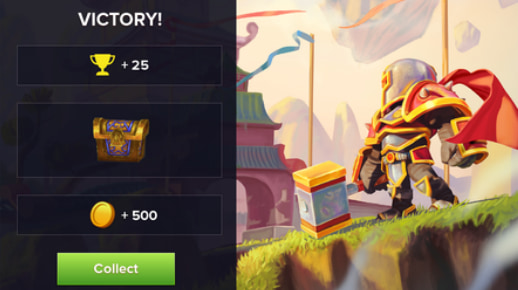

- Chests (Lootboxes): The primary reward delivery mechanism, won from battles. There were nine tiers of chests, containing all other key resources.

- Coins (Soft Currency): The primary resource earned from chests, used to upgrade Talents.

- Gems (Hard Currency): The premium currency, used to speed up timers or purchase items directly, like chests or Coin packs.

2. The Core Loop:

The gameplay loop was designed to be simple, rewarding, and endlessly repeatable:

Enter a Match -> Win the Match -> Receive a Chest -> Open Chest for Talents & Coins -> Spend Coins to Upgrade Talents -> Enter Next Match with Stronger Hero

3. Engineering the “Deficit”:

This is where the system’s elegance truly lay. The player’s primary dilemma was resource allocation. With a roster of heroes, they faced a constant, meaningful choice: Do I invest all my Coins into my main hero to make them exceptionally powerful, or do I spread my resources to keep 3-4 heroes viable for different team compositions?

This was not left to chance. I built a mathematical model that simulated player progression over two calendar years. By inputting data from competitor games—average session length, sessions per day, match duration—I could accurately predict the rate of reward acquisition for an average player.

Our model revealed two things:

- Our content plan was only sufficient for one year of engagement. My model allowed us to proactively plan for year two, ensuring long-term player retention.

- We could precisely engineer the monetization-driving deficit. We estimated that based on gameplay needs and the fun of experimentation, players would want to actively maintain 4 viable heroes. We then calibrated the economy to provide enough free Coins to fully upgrade only 2.5 heroes.

This 1.5-hero gap was our “golden deficit.” It was never a wall. It was a gentle, persistent pressure. We would fuel the desire to close this gap through personalized events that showcased other heroes, making players think, “I really wish my fourth hero was as strong as my main.” The option to buy a Coin pack with Gems was then presented not as a necessity, but as a welcome shortcut to achieving a self-motivated goal.

The Collision: When Reality Moves the Deadline

After a year of intensive development, our team was proud. We had a beautiful, intricate system. We had a fun core game. We had a team that trusted each other implicitly. We were on track for our scheduled publisher playtest.

Then the call came. The publisher was moving the playtest date one month earlier.

This was catastrophic. While our systems and code were ready, our presentation layer was not. For that final month, we had planned to implement the final UI and replace all our placeholder art assets. As a result, we went into the most important test of our project’s life with an unfinished, unprofessional look. The game world’s textures were ripped directly from Warcraft 3.

The consequences were immediate and devastating. As we would later learn, the publisher was running a parallel development track—a secret “bake-off” between our studio and another, both building a 3v3 MOBA. The other game, having weaker long-term retention metrics, had a polished visual presentation.

Our early retention numbers couldn’t compete. We lost the bake-off. The project was shelved.

But amidst the wreckage of the project, a strange and validating truth emerged from the data. Our system had worked perfectly.

The playtest analytics confirmed my mathematical model with chilling accuracy. Player engagement, the 2.5 vs. 4 hero dilemma, the points of monetization friction, the conversion rates—it all happened exactly as designed. We had successfully built a deep, engaging game with a highly effective soft monetization economy. But it didn’t matter.

The Autopsy: Why a Perfect System Wasn’t Enough

This is the central lesson of the Playtagon case study. Why did a “mere” visual factor completely negate a successful core loop and a validated economic design?

The answer lies in the brutal, unforgiving nature of the First-Time User Experience (FTUE).

A player’s decision to stay or leave is made in minutes. In that critical window, they are judging the product’s quality and promise. A game with placeholder UI and ripped assets from a 20-year-old game doesn’t signal “deep and rewarding gameplay ahead.” It signals “cheap, unfinished, and untrustworthy.”

A psychological disconnect occurs. You can have the most brilliant game balance in the world, but the player will never experience it if they churn on Day 0. We had meticulously polished the flow of our FTUE through focus groups, but we failed the feel.

- Problems in your meta-game or economy affect your D7, D14, and D30 retention.

- Problems in your FTUE visuals and presentation kill your D1 retention.

We had built a magnificent engine, but we showed it to the world without a chassis. No one cared how beautifully the engine ran; they just saw a pile of parts.

From Pain to Power: The Lessons That Forged a Career

An experience where your best work is invalidated by external factors can be crushing. Or, it can be a crucible. For me, it was the latter. The hard-won lesson of Playtagon directly shaped the specialist I am today.

- On System Design: Vindicated Belief. The experience was a powerful real-world validation of my belief in player-friendly soft monetization. It proved that you can build fair, non-coercive systems that are also highly profitable. I learned the nuances—the critical importance of honesty and the careful balance between linear and probability-based rewards.

- On Analytics: Forging a Hard Skill. The most painful part of the experience was my inability to effectively argue against the premature playtest. I knew it was a mistake, but I lacked the hard data and communication skills to prove to management why it would fail and what the outcome would be. It was a moment of perceived incompetence that I vowed never to repeat. This drove me to make deep data analytics my primary hard skill, a focus that defined my next role and led me to establish an R&D department. Today, I can state with confidence the expected outcome of such a decision and defend it with data.

- On Management: The Primacy of Trust. The “first storm” that sank our project was enabled by a crack in the foundation of trust between the team and leadership. A team needs to trust that leadership will protect them and give them the time to do their best work. Leadership needs to trust the team’s expertise. When that trust is fragile, the first external pressure will break the project apart.

Key Takeaways for Game Developers, PMs, and Leaders

This story is not just my own; it contains universal lessons for anyone in this industry. If I could distill this entire experience into three pieces of advice, they would be these:

- For System Designers: Your job is a paradox: make the game profitable while making players love it. To succeed, you must become a master of player expectations. Understand the unwritten rules of your genre and innovate within that framework. A brilliant system that violates player trust or genre conventions is a failed system.

- For Product Managers: Know your KPIs intimately. Understand that a beautiful UI impacts D1 retention, while a deep meta-game impacts D30. You are the custodian of finite resources. Your primary skill is to prioritize ruthlessly, applying resources to the features that will have the maximum impact at the right stage of development.

- For Studio Leaders: Trust is your most valuable currency. Hire experts and then empower them to execute. Your vision must be a rock. Changing the product’s core direction mid-stream creates “development hell,” wastes money, and demoralizes your best people. You are the carrier of your company’s DNA. Protect it, believe in it, and create an environment where great work can actually see the light of day.

The story of Playtagon is a painful one, but it is not a tragedy. It’s a powerful reminder that in game development, you can do everything right and still fail. But if you have the courage to perform an honest autopsy, the lessons you learn from that failure can become more valuable than any success.

This article was originally published on artemzaporozhets.com